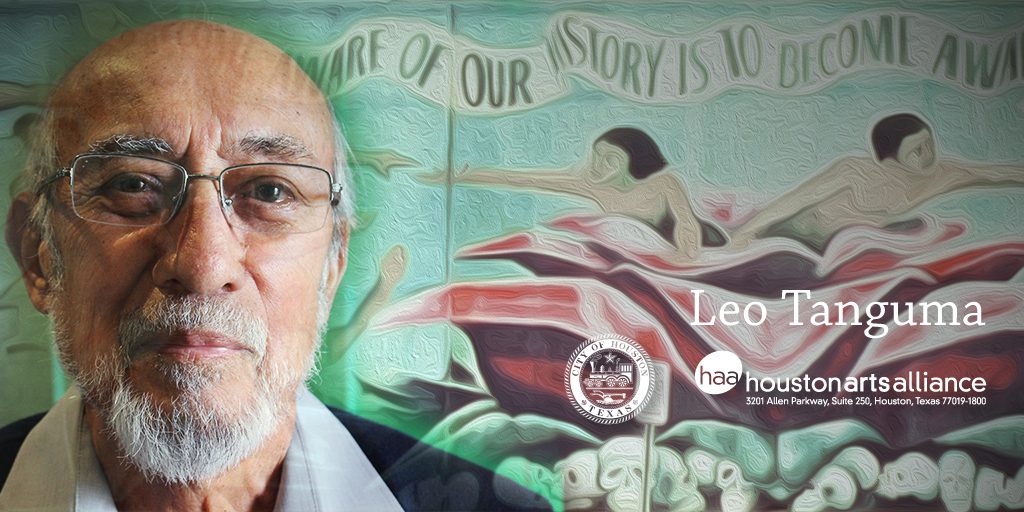

Few people know that one of the most iconic murals that reflects the struggles of Mexican-Americans during the 1960s and 1970s is located in the historic East End neighborhood of Houston. The creator of this massive 240-foot mural is a self-made artist from South Texas. His name, Leopoldo Tanguma, better known as Leo.

Artist and muralist Leo Tanguma was born to Texas farm workers with Mexican ancestors in Beeville, Texas, a small rural town located between Corpus Christi and San Antonio.

He started his life-long art career at the very young age of eight using a pencil and pieces of cardboard boxes to draw people working in the fields with his parents. He was inspired to create art by the hardships endured by Mexican-Americans.

This is Leo describing his entry into artistic expression:

Leo recalls creating his first mural in elementary school in the early 1950s. While waiting in his 5th grade classroom for a substitute teacher, one of his classmates asked him to draw him killing the local sheriff on the blackboard. According to Leo, the Beeville sheriff was known for his brutality against Chicanos and had killed a number of Chicanos including a close relative of his mother.

As expected, the blackboard mural of the sheriff being stabbed by Leo’s classmate excited the fifth graders and received their support. When the substitute teacher arrived, she ordered Leo to erase the “offensive” drawing. Then she proceeded with the punishment: hit him on his back with a ruler.

This early childhood incident inspired Leo to get involved in community matters and the struggle for social justice. Art became his voice to proclaim the aspirations of the oppressed and a means to protest peacefully.

By the mid-1950s, Leo’s parents were deeply rooted in their environment in the small rural town of Beeville, Texas. He quit school in the sixth grade to help support the family by doing field work. Subsequently, his older sister, Dina, became motivated to explore opportunities elsewhere. She encouraged Leo, who was 14 years old, to move with her to Pasadena, Texas where he worked as a custodian in various places.

Years later, Leo served in the Army. While stationed in Fort Ord, California and Germany, Leo painted a number of murals. After being honorably discharged, Leo enrolled in Lee College located in Baytown, Texas. During this time, his awareness of Chicano issues increased. At one point, a professor who assumed Leo was an immigrant questioned him about Mexican’s perceptions of Americans. Leo said, “In my country, we see you as racists, as invaders.” Then, Leo added he was born in Texas and, “that is how as we in the U.S. and in the minority communities see you.”

In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, the Chicano Movement was sweeping across the Southern states. The movement encompassed fighting for the restoration of land grants, farm workers’ rights, voting and political rights and more. The Chicano Movement also addressed reversing negative stereotypes of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in mass media.

The Chicano Movement set the right tone for Leo’s most iconic art piece in Houston: Rebirth of Our Nationality.

The huge 240′ wide by 18′ high mural was completed with the help of friends and local university students in 1973. While Leo painted, he dialogued with people in the predominately Mexican-American neighborhood about the mural theme of Chicano cultural and historical identity. The mural design encouraged the community to understand the struggles of Chicanos against racism and injustice.

In the beginning, funding was a major obstacle. The Houston Chamber of Commerce secured the mural site on Canal Street to encourage Chicano participation in their activities. They eventually obtained a donation of 100 gallons of paint and some supplies. They did not provide any funds to compensate Leo or the other artists for their work on the mural. Leo completed the mural after a year and a half, working for free at great financial hardship to his family.

Once completed, viewers greatly appreciated the mural’s basic artistic elements such as movement, balance and proportion. Following are some of the highlights:

- In the center of the mural a young Chicano couple emerges from the petals of a large red flower and reaches out to each side to accept offerings from the other figures. People from both ends move towards the center to give the couple their experiences in the struggle for social and human justice.

- A woman with her hands dismembered symbolizes domestic violence and repression against women. Slightly above, is the figure of a young girl, who has broken the sword that cut off the woman’s hands and heroically grasps the broken sword in a gesture indicating that she is resolved to fight against abuse.

- Two Mexican “campesinos” hold the Plan de Ayala, a document drafted by Mexican Revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata in 1911. This Plan supported land reform and revolutionary ideals.

- The book without pages reflects the unwritten writings and art works of Mexican-Americans. In Leo’s words, “Writers and artists lost their opportunity to develop and share their art when they were forced out of their lands and discriminated against. The man without a face is precisely the artist who never developed and never had a chance to exist.”

- The man holding the United Farm Workers’ flag and contract is a member of the United Farm Workers Union that was led by Cesar Chavez. This flag was an important symbol of resistance during the Chicano Civil Rights Movement of the 1960’s and 1970’s.

- A teacher is holding a book and symbolizes the importance of education in the community, an issue still presents today.

- The images of Mexican-American soldiers holding out their medals depict the many Latinos who fought bravely in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. Next to them is a grief-stricken woman holding a telegram notifying her that her son has been killed in any of these wars, while she clutches his framed photograph.

In 2013, Harris County bought the former Continental Can Company Building that had the greatly deteriorating Rebirth of Our Nationality mural on its south facing wall. After years of discussion about restoring the mural, Harris County issued an Artist’s Call for Entries to re-do the mural. GONZO247, famous Houston aerosol artist, was selected and began work on the project in 2017 with Leo Tanguma assisting as a consultant, since he had moved to Denver, Colorado in 1983. Harris County officials provided $105,000 in funding for this project as the mural was very meaningful for the East End community.

In June 2018, the art, community and civic leaders gathered at the County Office Building at 5900 Canal Street for the unveiling in front of the mural.

Leo Tanguma is astonished when he reflects on painting the historic piece freehand as no grids or projectors guided his work on the enormous wall.

When asked about what makes art and an artist successful, Leo reflects on his views about the community:

At age 77, Leo continues to create murals in schools, universities and many other sites. Of particular importance is his mural, In Peace and Harmony with Nature that he completed at the Denver International Airport in 1995. This eye-catching piece has captured the attention of travelers and art critics, who describe the mural as one that “exudes his Mexican heritage, world history, spirituality, and progressive social ideals.”

![]()

This story is funded in part by the City of Houston through Houston Arts Alliance.